HOW I MET STANLEY KUBRICK

One day a couple of months later, Mr. Harlan sent me to Abbots Mead, a house beyond the outskirts of northeast London. It was halfway along Barnet Lane, a tree-lined road that ran alongside the parish of Elstree and Borehamwood.

There was a closed metal gate with no bell. I tried pushing it, and it opened slowly. I parked the car in the gravel courtyard under the branches of two large trees. I rang the bell, and a rather tall lady with a big smile opened the front door. She introduced herself as Kay, a secretary.

“Are you Emilio?” she asked. “Do you know who you’re working for?”

“Yes, for Hawk Films.”

“There’s someone who would like to meet you. He’ll be here in a moment.”

A few minutes later, two golden retrievers came through one of the doors in the corridor followed by a brisk-looking man of about forty.

“Good morning,” he said holding out his hand.

“Good morning,” I replied. We shook hands. He was slightly taller than me and had an impressive, curly black beard. He looked like Fidel Castro.

“I’m Stanley Kubrick,” he said, looking me in the eye.

There was a moment of silence. Maybe I was expected to say something. I didn’t say anything, apart from: “And I’m Emilio D’Alessandro.”

Without letting go of my hand, he took a press clipping from his pocket.

“Is this you?”

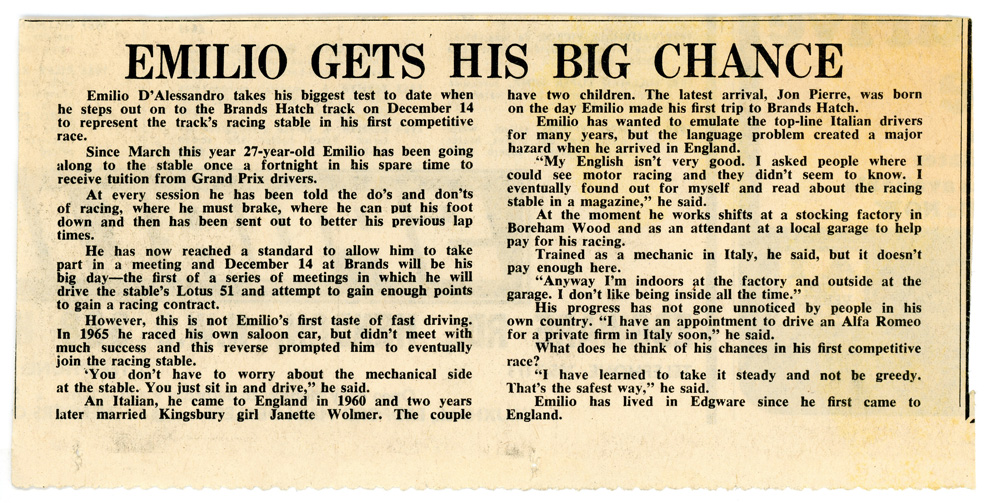

It was an old article from 1968 describing my career as a Formula Ford driver.

“Yes, it’s about me,” I answered.

“Do you drive like that on the roads, too?”

“No, you must be joking! Only when I was on the circuit.”

“Do you respect the speed limit and road signs?”

Was it a trick question?

“Of course,” I replied, “I have to respect the highway code. Any infraction would be reported on my racing driver’s license, too. I would lose points, and my score affects my rating. I even have to be careful where I park.”

A smile appeared through his beard. “I have a Mercedes 280 SEL automatic. Do you think you can handle it without a problem?”

“It’s a car that does half the work for you. I think I can manage the rest.”

“Let’s try, then. Why don’t we have a night out with my family at the Royal Opera House and you drive us?”

He took his leave and went back into his room followed by the dogs. Before he closed the door, I caught a glimpse of a cat yawning and stretching on the desk. I smiled.

The secretary explained to me that this man, Stanley Kubrick, was a famous American film director who had been living in England for some years. I had never heard of him. Those days I never went to the cinema. I didn’t have time. I’d driven a great many actors, actresses, and producers, but that’s as far as my knowledge of the world of film went: handshakes and tips. I only ever got to see actors in the flesh.

“Are you pleased that you’ve met him?” asked the secretary.

“Well,” I blurted out, trying to think of something polite to say, “I’m pleased that he’s an honest and respected person. That means he’ll treat me well, too.”

STANLEY KUBRICK’S SYSTEM OF RULES

Stanley had devised a system of rules to ensure that Abbots Mead worked perfectly. All we had to do was follow them to the letter. I realized this practically immediately when he advised me never to trust hotel receptionists or the concierge when I was delivering documents. I should always place them in the hands of the person they were addressed to. He did everything he could to avoid problems arising. And he didn’t care for idle chat: after telling us what we had to do, he would just leave notes on our desks about routine tasks.

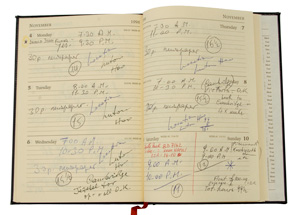

Stanley didn’t waste anything. But he wasn’t bothered about saving, either. He woke up at ten or eleven, sometimes at midday, and he went to bed very late so that he could take full advantage of the opening times of Warner Bros.’ offices in America. Andros, Margaret, and I started work early in the morning, while Stanley was still asleep. We dealt with the tasks he had left us just a few hours earlier before he went to bed. When he woke up, everything was done and we started all over again. It seemed like a never-ending cycle, because it was.

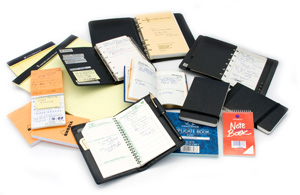

We had all received a kit with everything we needed. Mine was a briefcase with all the maintenance and insurance documents for the Mercedes and the other cars, as well as every other document I might need while I was running errands. Taking a traveling office everywhere you went reduced the risk of having to go back to base and waste time. Stanley did the same, stuffing his jacket pockets with pens, photocopies, sheets of paper, recorders, and tapes.

My pockets were full, too. I carried two note pads, a small one and a large one, two pens (one was a spare), and my day timer, which was a datebook with a weekly planner on each page. There I wrote names, office addresses, appointments, telephone numbers, and the prices of various things. The notepads were chosen to fit in the breast pockets of my shirt. Stanley had been very clear about shirts: I was to use only shirts with two breast pockets. In the right pocket I kept the notepad, notes he gave me, and receipts. In the left one I kept cash, my driving license, and other ID. The pockets had to be button-down so that nothing would fall out if I bent over. He also asked me to make sure I always had five hundred pounds in my wallet to cover any expenses I incurred during the working day. If I spent any money, I had to go home and replace it so that I always have five hundred pounds in my pocket.

The equipment for the car consisted of a first aid kit, a flashlight, a lighter, and more pens here and there. We also carried three thirty-meter ropes just in case we came across an injured or abandoned dog (Tie up the dog, take it to a vet, then back to Abbots Mead, and find a reliable person to give it to). There was also a muzzle to use if the dog was nervous, and for the same reason, thick leather gloves, too. The gloves also came in handy if we found a particularly angry cat.

TRAVELLING FOR BARRY LYNDON

The incessant search for suitable film locations spread like ripples in a pond after a stone has been thrown in. Ken went farther and farther away from Abbots Mead until he reached Ireland. The hills and historic buildings around Dublin seemed indispensible, especially as much of the story was set in the Irish countryside. Stanley had no choice: he had to leave England.

In the summer of ’73 he planned the vast removal operation. Each production department was given a couple of vehicles to move all their material, and Stanley chose someone to be responsible for the whole process. Christiane and the girls were responsible for the dogs: an entire carriage on the train to Dublin was booked for Phoebe, Teddy, and Lola. Margaret was to look after the seven cats. She stayed in Abbots Mead to keep base camp operational. There was an incredible amount of material to move: ten cameras, lenses, filters, dozens and dozens of lighting rigs and lamps, hundreds of costumes, and reels of film. Once everything was packed and loaded, actually transporting it all didn’t take long, because Stanley decided to move everything at once to waste as little time as possible. One after the other, semi-trailers, trucks, vans, and buses drove through the gates of Abbots Mead and Radlett in the direction of Dublin. When the tail of this huge serpent on wheels left, its head was already halfway there. Most of the equipment and material was loaded onto the semis, but Stanley asked each department to take the bare essentials for two or three days work with them in their minibuses. That way they could get started as soon as they arrived in Dublin.

Jan left with his wife and children. So did Andros and the production assistants. I watched the courtyard at Abbots Mead empty out and wondered what Stanley had in store for me. Should I have suggested a radical change like this to Janette and the kids?

“No, you’re in charge of transport.”

Stanley and the others were near Dublin, and Margaret couldn’t leave Abbots Mead, so someone had to make sure the two locations kept in touch efficiently.

My first trip in a rented Ford van was with some photographic equipment. There was a well-equipped studio in Dublin, but Stanley wanted to use his own cameras. After that, I spent a week collecting private mail from the Borehamwood post office. I took the post together with some sealed envelopes that Margaret had given me, and headed north.

During my trips I took a variety of documents to Ireland: authorization from the lawyers to start work on the film, the payroll ledgers the accountants had prepared, and the insurance contracts drawn up by Margaret. I took a few vanloads of furniture and props that had either been rented or commissioned in London. On the way back, the vans were full of material that was no longer needed in Ireland and could be stored in the warehouses in England. I even had to take dozens and dozens of boxes of candles. Stanley and John had decided to use these to light the indoor night scenes; they wanted to use spots and other electric lighting as little as possible.

I traveled by land, sea, and air. The plane took about an hour plus check-in time. By car or van meant taking the ferry, so it took all morning or afternoon. By train, it took just as long, though it was much more comfortable – I could have something to eat and relax; it was like being in a hotel room. However, it was a luxury I didn’t often get the chance to enjoy, because everything became increasingly urgent. The worst trips were those by sea. I detested the ferry. I spent the three-hour journey clinging to the handrail with my eyes closed, deafened by the sound of the waves crashing against the windows, and praying that I would touch dry land again.

At Heathrow Airport, I used open tickets, which meant I could take the first available flight. Margaret had managed to negotiate favorable conditions with the airlines thanks to the large number of bookings that Hawk Films made. Anyone who spent time in Heathrow during the autumn of 1973 would have heard this announcement: “Emilio D’Alessandro to contact the office.” The announcement was made every fifteen minutes, along with others giving news of delays or which gate to go to. I knew it meant that I had to contact Margaret. It was her idea: I would hear it as soon as I reached the check-in area and knew that I had to get in touch with the Lodge straightaway. On my way to the gate, I went past the airport staff notice board. Among their messages were notes Margaret had left for me by phone, with details of where to pick up various material and who to contact when I got there. I tore these notes off the board, stuffed them in my pockets, and hurried along.

THE OVERLOOK HOTEL SCRAPBOOK

Every year at Christmas, Stanley sent me to deliver gifts to the homes of his friends and assistants in London. The package for Alexander Walker was particularly large and heavy that year. When I arrived at his flat, the concierge told me that Alex was on holiday in Switzerland, so I informed Stanley that I hadn’t been able to deliver the gift. When I tried again some days later, Alex was very cross.

“Do you know what Stanley did?” he said, before I could utter a word. “He looked for me while I was in Switzerland. He called around all the hotels until he found me. Then he kept me on the phone for ages to get me to do a job for The Shining. Did you tell him I was in Switzerland?”

“Well, Alex. . . Yes. But I didn’t think –”

“On holiday. You see? He doesn’t even respect the Christmas holidays!”

I didn’t dare answer back that I hadn’t had a Christmas holiday since 1970. Instead I made some throwaway remark along the lines of, “Well, you know, that’s Stanley for you,” in an attempt to calm him down. Alex took the gift and went indoors.

Anyway, Stanley’s phone call to Switzerland was a success, because some weeks later Alex agreed to help Stanley by compiling a scrapbook of newspaper cuttings from Colorado. He used his skill as a journalist to put together articles that described the mysterious past of the Overlook Hotel, filled with inexplicable accidents, unexpected suicides and escaped criminals. Stanley gave Alex 35mm microfilms containing fifty years of front pages from the Denver Post and the Rocky Mountains News. He also gave him the light box, which was as big as a fridge. Alex had no small amount of difficulty making space for it in his flat. Finally, after six weeks spent inventing headlines for imaginary news in the style of these two turn of the century newspapers, the job was done. In the end, the sequence where Jack looked through these articles was never actually used in the film. Working for Stanley could mean that too.

STANLEY KUBRICK’S BOXES

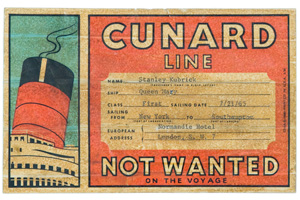

After the family had moved from Abbots Mead to Childwickbury, it was time to find a place for all Stanley’s stuff. The Stable Block was a square building with an internal courtyard. It turned out to be a good place to store Christiane’s artist’s materials that couldn’t fit into the main house. Stanley used the large room on the right to hold the trunks where he stored everything he’d kept since he had started making films. There were hundreds of them, a pyramid of trunks made of wood or steel. They were green, black, big, even bigger, and enormous. The sight of them heaped up in the courtyard of Childwickbury was, to say the least, impressive. Most of them contained the things Stanley had brought with him by ship when he moved from the United States to England, and they hadn’t been opened since then. There were various objects, books and other odds and ends he’d had in his apartment in New York, as well as all the production material from the films he’d made in America. Some of them were still sealed with the string and labels of the Cunard Line, the transatlantic shipping company Stanley had traveled with in the sixties. All Stanley’s American life was in there.

Before Stanley decided to move them all to the new house, they had been stored in two rented warehouses in Bullens and Bushey. They had been there for at least ten years, in no particular order, with just a number to identify them. The inventory had long since been lost, so every time we he had took for something it was a disaster.

Andros and I would pick up a trunk, took off the shipping company label, and opened it up to see if what Stanley was looking for was inside. More often than not it wasn’t. So we had to open another one. Stanley usually asked us to find books or magazines. The instructions he gave were sometimes rather vague: “Look for a big black trunk with metal edging.” Fortunately, at times he was more specific: “Trunk number 150.” All this was fine until we discovered that either there were at least twenty big black trunks with metal edging or that trunk number 150 didn’t actually exist.

Together with Andros, during these visits I started making a list of the contents of every trunk we opened in an attempt to gradually reconstruct the lost inventory. There were old issues of Look, old issues of other American magazines, newspaper cuttings, contracts with United Artists, data sheets of the personnel on the set of some old film, Stanley’s high school diploma photo, letters from lawyers, letters from assistants, letters from admirers, other letters, books, big books, small books, and various other stuff.

When we got back, we would show Stanley the list. He would look at it and decided what to keep and what to throw away: “Get rid of it! But keep the trunk. We’ll use it for something else.”

After what had happened in the past, this time, since there was plenty of space, I asked Stanley to store the trunks more methodically. He asked me what was making it difficult to find the right trunk. “Finding it!” I answered. I suggested we put them in rows and give a letter to each row. “The trunks are already numbered, so it will be a bit like battleships. We’ll be able to find them easily like that.” “Right,” agreed Stanley, “and what’s the second problem?” “Getting to the ones at the bottom of the pile.” I suggested that instead of putting the trunks on top of each other, we put each one on a shelf.

“Emilio, let’s do an inventory. What do you think?”

“Sorry, Stanley. No way.”

“Perhaps I could get someone else to do it.”

“Whatever you want. But I don’t even want to hear his name mentioned, okay?”

PHOTOGRAPHING CHRISTIANE KUBRICK’S PAINTINGS

The home photography studio that Martin Hunter and I had build in Anya’s bedroom was inaugurated later, at the end of the eighties, when there was an opportunity to publish a book about Christiane’s paintings. Some of her pictures had been sold, but many were hanging in the house or stored in the Stable Block. The time had come to produce a complete catalog of her works.

Stanley had reached an agreement with Warner for the publication and distribution of the book. Christiane was working with the Sunday Times art critic to decide which works to choose and what to write in the introduction. Martin had just left Childwickbury to go back to America to work, so there was no longer an official photographer at the Kubrick home.

“Emilio, do you think your daughter might be interested?”

Thanks to a course organized after school by one of her teachers, Marisa had been enthusiastic about photography since she was a teenager. When she was eighteen, she went to study at the Ealing Technical College & School of Art, but she left the course because it wasn’t creative enough for her. She didn’t want to know all about the history of photography; she wanted to understand the creative process that lies behind a perfectly taken photograph. At the beginning of 1984, she got a job as an apprentice at Charles Green’s studio in Edgware. There she improved her ability to “paint a portrait by illuminating the subject,” as she once described it to me enthusiastically. Green also taught her a lot about developer baths and post production in general. Getting her hands dirty and being involved in every step of the process is what Marisa had always wanted to do. When we were talking in his office, Stanley often asked me how Marisa was getting on. I told him that she had decided to start work as a freelance photographer and was getting plenty of assignments from Cameo Photography and Hills & Saunders, two of the best portrait photography studios in London. During the three years that she worked for them, Marisa had the chance to photograph members of the Royal family and pupils at Eton College as well as lords and ambassadors at their country homes. In 1989, she became a member of the British Institute of Professional Photography. She was the youngest girl ever to have achieved that status.

“I don’t know. Give her a ring,” I had answered Stanley.

“What do you mean, ‘Why are you worried?’ Dad!” she said when she called me that evening to tell me about the offer. “He asked me to take photos of his wife’s paintings. That’s not my field! I’m specialized in portrait photography. I don’t know if I can do it. And what’s more . . . you’ve seen the photography in Barry Lyndon, haven’t you? How can I live up to that?” Marisa had always regretted that she had never had the chance to watch Stanley and John Alcott at work on that film. She was only ten at the time. Barry Lyndon was the only one of Stanley’s films that she mentioned continuously. John’s ability to work with light and composition, as well as his sense of history, had moved her deeply. Light and composition were the fundamental elements of all photography, and she always said, “Every single frame of that film is a unique, perfect photograph.”

“Marisa, if you don’t feel up to it, say no. It’s not a problem,” I said, in an attempt to calm her down.

“But I want to take those photos!”

“Good. Then you’re ready.”

Marisa went to Childwickbury. Stanley briefed her about the job, he showed her the Wista camera, and took her upstairs to the new photographic studio. Christiane’s works were oil paintings, etchings, and charcoal drawings, so different photographic techniques would be needed to reproduce the colors accurately.

In the end, Marisa, braced herself and decided to accept the job. She asked me to help her move the paintings, while her boyfriend gave her a hand with the Wista from a technical point of view. They spent a couple of days trying out different types of film, exposures, and lighting with the Lowel rigs that Stanley kept heaped up in the cellar at Childwickbury. Once she was satisfied with the test photos she had developed, she finished the job in less than a week. Stanley and Christiane were impressed, and sent the pictures to Warner to be published.

In 1990, Christiane Kubrick Paintings reached the bookshops. “Emilio, go to London and make sure the book is displayed properly on the shelves.” When I went to Foyles or Dillons, I only found a few copies of the catalog, and they were hardly ever on display. If I asked the shop assistants why this was, they told me that the book had quickly sold out. When I went back to Childwickbury and told Stanley about the excellent sales, he didn’t comment. He picked up the phone immediately and called Julian: “Call Warner and tell them to print more copies of the book. They’ve already run out in London.” Sometimes he only seemed happy when he had managed to solve a problem.

MEETING TOM CRUISE AND NICOLE KIDMAN

“Emilio, come here. I want to introduce you to my actors!” said Stanley over the intercom. I knew hardly anything about the film that he was going to start work on in just a few weeks’ time, just what he told me when we had met in spring. He was standing in the corridor on the ground floor beside two well-dressed, smiling young people. “Can you take them outside? The driver is waiting for them in the courtyard,” he said, withdrawing to his rooms. He had clearly intended to leave us alone. Tom and Nicole asked me if I was married, if I had children, and as usual, what it was like to work for Stanley.

“Just fine,” I replied. “Everything has always worked just perfectly.”

“But have you really been working for him for over twenty years?” Tom asked.

“Since the end of 1970.”

“Congratulations for being with Stanley for such a long time,” remarked Nicole.

“And just think, I’d sworn to be faithful to my wife.”

“What do you think of the sweet couple?” said Stanley, when I went back to his office.

“Very kind and polite. What do you think?”

“I get on well with them.”

Rather late that evening, Stanley gave me a sealed envelope with the script of Eyes Wide Shut and asked me to take it to Tom and Nicole. “If they’ve already gone to bed, lean it against their bedroom door so that when they wake up, it will fall on their feet.”

Stanley had rented an apartment for Tom and Nicole on the first floor of a house on the other side of Well End. I knew it all too well: that was where I had seen Stanley’s crew at work, surrounded by cats, for a scene from A Clockwork Orange, for the very first time, twenty-six years ago. It was like going back to the beginning again. When I reached the gate of the house, the security guard stopped me. The Cruise family could not be disturbed. When I pointed out that the reason I needed to pass was because Stanley Kubrick had sent me, he replied that his employer, Tom Cruise, had put him there precisely to avoid intrusions of this kind. “Listen,” I said, in an attempt to break the deadlock, “I know the owner. Every year I bring him a case of whiskey on Stanley’s behalf. I know the house, too. I know it so well that I know which steps of the wooden staircase creak. I could make my way to Tom and Nicole’s bedroom door without anyone hearing a sound, and that is where I have to go. Trust me, and trust Stanley Kubrick, who sent me.”

The following morning, I found something from Stanley, too. There was a sealed envelope on my desk: “Please stay around because at noon I have to be at Tom Cruise’s house. Make sure we take the Rolls.” It would be the first time that I had driven the new car.

When we arrived at Tom and Nicole’s, Tom came down to meet us in the living room, and Stanley asked him if he had read the script.

“Yes, I found it outside the bedroom door. Who left it there?”

“Emilio,” Stanley replied.

“But . . . how did he get past the security?”

“Mission is possible.”